The Key Figures in the Development of Satta Matka

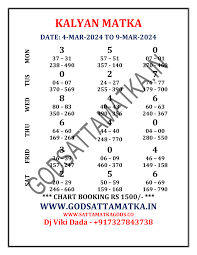

Development of Satta Matka Satta matka is a popular form of gambling in India that has evolved over the years to meet the needs of its players. The game has incorporated many modern methods while retaining its original essence, making it unique […]

Development of Satta Matka

Satta matka is a popular form of gambling in India that has evolved over the years to meet the needs of its players. The game has incorporated many modern methods while retaining its original essence, making it unique in the world of gambling. Its popularity reflects the aspirations and spirit of Indian people. Its enduring allure can be attributed to its ability to adapt to changing societal and economic conditions. Despite its allure, it is crucial for players to play responsibly and avoid becoming addicted to the game. Moreover, they should be aware of the legalities and risks involved in online gambling.

The evolution of satta matka can be attributed to the changing social and economic circumstances in India. Its popularity during the time of the textile mills was fueled by the need for an exciting pastime to relieve stress and monotony. Many mill workers were also keen on accumulating large amounts of money, which could be used to fulfill their financial goals and aspirations. The game soon gained traction in the city of Mumbai, where numerous textile mills were located.

During this period, the game was played by mill w, orkers and their families as a way to spend their free time. It was also an opportunity to earn big money in a short amount of time. In order to win, the players had to predict the opening and closing rates of various imaginary products. This was based on a random selection process of numbers or using a deck of playing cards. The winning number was declared at set times, which were called “sattas.” The sattas were drawn by a group of specialists called ‘matka kings’ or bookmakers. These bookmakers were able to predict the results of the satta and make large profits for their clients.

The Key Figures in the Development of Satta Matka

In the present day, satta matka has taken a more sophisticated approach to number selection. This has resulted in a greater element of skill and strategy, while still maintaining the excitement and unpredictability that has always been associated with the game. It has also been adapted to the convenience of users by being made available on various online platforms.

The development of satta matka is an ongoing journey, shaped by changes in society and the emergence of new technologies. A Satta matka development company must constantly innovate and keep up with the latest trends to remain competitive and stay relevant in the market. To achieve this goal, a satta matka development company must invest in research and development to develop innovative games that can attract the attention of players and boost its revenue.

A Satta Matka Development Company must also focus on building a strong brand image and reputation. This will help to establish the company as a leader in the industry and increase customer loyalty. It must also strive to deliver a high-quality product and provide excellent customer support to ensure that its games are as enjoyable as possible. This can be achieved by regularly updating its existing games to incorporate new features and content.

Related Posts